France has all the natural resources and know-how to rival the British when it comes to the art of distilling world-class whisky and gin…

Why must the Scots have the monopoly on whisky? And why, for that matter, must the English have the monopoly on gin? All over France there are highly skilled distillers producing excellent varieties of both spirits – many of which would happily rival their British counterparts.

The revolution apparently started back in the 1980s with a distillery in Brittany, called Distillerie Warenghem. Here, in 1983 to be precise, they produced what they claim is the very first French whisky – ‘an entry-level blended whisky’. Since then, dozens more distillers have jumped aboard the bandwagon. Among the notables are Celtic Whisky Distillerie (also in Brittany), Distillerie Lehmann (in Alsace), Rozelieures (in Meurthe-et-Moselle), and Brenne (in Cognac).

According to the Fédération du Whisky de France, there are now no fewer than 100 whisky distilleries across the country, and 115 different brands. Why so many? Well, the French are, per capita, one of the largest consumers of whisky on the planet, so it makes sense to distil plenty of the stuff domestically.

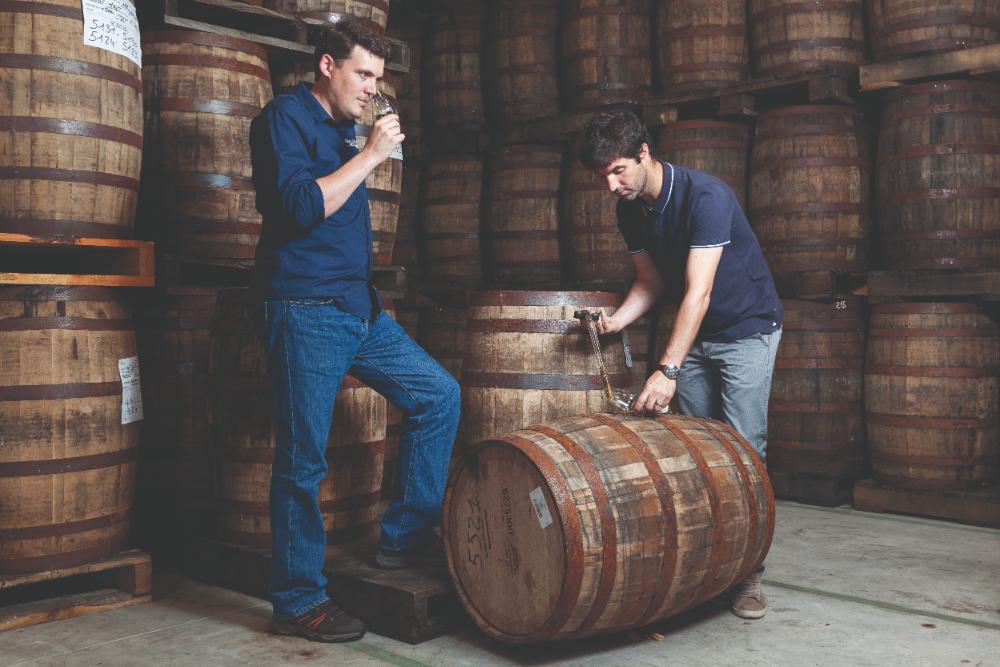

David Roussier is the director of Distillerie Warenghem. He admits that when his father-in-law first launched, it was “a huge gamble”. “One has to remember that, at that time, there were no distilleries in Europe apart from Ireland and Scotland,” he says. “For a small distillery like ours, there was a big risk of losing everything. But thankfully it turned out to be a success.”

Indeed it did: Warenghem now sells 400,000 bottles a year, two- thirds of that single malt. And, according to Roussier, the terroir and climate of Brittany are perfect for distillation. “Brittany has two main things to offer: its climate and its water,” he explains. “The climate is pretty similar to the one in Scotland but slightly warmer. That has an impact on maturation. And the water in Brittany comes from a shale and granite soil, which give a very pure water.”

Jonas Vallat is brand ambassador at Rozelieures. With a history of distilling eaux de vie, and of farming fruit and cereal, he says his company was perfectly positioned to move into whisky. The founder, Christophe Dupic, first struck upon the idea after returning from a trip to Scotland. “While harvesting a field of barley, he suddenly realised he had everything he needed to produce whisky: water in sufficient quality and quantity, an abundance of cereal crops, a distillery equipped with two iron stills, and a long tradition of blending spirits and ageing them in wood.”

Now, 23 years later, Rozelieures is one of the world’s few distilleries to manage all the stages of whisky production on site, from growing the barley and preparing the malt, to brewing, distilling and bottling. Vallat believes it’s natural that the French are so skilled at making whisky. “France has everything it needs to be a great whisky nation,” he says. “Historically, we have all the know-how we need to produce it. And France is the world leader in the production of malt. Our skills in distillation and production are well proven. After all, our cognac, armagnac and calvados already enjoy a great global reputation.”

Down in Cognac, the whisky brand Brenne has an intriguing back story. Founded and run by an American former ballet dancer called Allison Parc, its whisky is aged in a combination of Limousin oak barrels and reused cognac barrels. “It offers a breadth and depth of unique flavours that other French whiskies don’t, including crème

brûlée, bananas and fresh blueberry muffins right out of the oven,” a spokesperson explains. Parc distributed her first bottles in New York City in 2012. Over a decade on, her creation is now sold across France and worldwide, having garnered several awards.

What about French gin? An incipient form of the spirit first came to the fore back in the 1700s when King Louis XVI lent his royal support to a distiller of genièvre, a continental version of gin. As in Britain, industrial distillation initially dominated the market – until recently, that is, when there was a resurgence of artisanal distillers, making use of locally grown botanicals.

The beauty of botanicals

One such gin-maker is Audemus Spirits, based in the town of Cognac, which began distilling in 2013. The founder, Miko Abouaf, has even produced a gin with Michelin-starred chef Anne-Sophie Pic. “We only work with natural ingredients – nothing artificial,” Audemus director Ian Spink explains. “And we strive to capture the true flavours of our botanicals. The process of crafting gins in this way is painstaking and takes months of experimentation, distilling each ingredient individually to find the right temperature and pressure in order to extract the perfect flavour profile.” Much like in the Anglo-Saxon world, the French traditions and etiquette of drinking spirits have loosened in recent years. Many will still drink whisky straight or with ice or water. Both whisky and gin are particularly popular in long drinks and cocktails. And, again, like the Anglo-Saxons, there are no longer conventions on when either spirit might be consumed. Lunchtime aperitifs? Pre-dinner cocktails? A nightcap? Anything goes. At Audemus, Spink explains how the French are only just starting to discover gin’s endless possibilities. “The trend for gin here is on the rise; consumer interest is growing in a way that it did in the UK some five years ago, he says.

Gin as a palate cleanser

He adds that the spirit is often served with tonic in bistros and cafés, but also in cocktails in France’s burgeoning cocktail bar scene, “One difference here in France is that a G&T will often be served as a digestif, after a meal where wine has been served,” he adds. “It’s seen as a palate cleanser or refresher. Sometimes people will continue with G&Ts as the night carries on, or they’ll return to wine after a single refresher. It’s the biggest difference to the way in which gin is consumed in the UK, and it’s quite charming.”

Among whisky drinkers, certain trends remain. David Roussier at Distillerie Warenghem says most French drink it as an aperitif before dinner or a digestif afterwards. Jonas Vallat, at Rozelieures, suggests: “Older drinkers tend to drink whisky neat as an aperitif, while younger drinkers opt for cocktails.”

Perhaps it’s best just to let drinkers decide for themselves. As the good people at Brenne say: “Like everywhere in the world, the way whisky is enjoyed depends mostly on the individual who is enjoying it.” Quite right too.

Latest Posts:

- A bluffer’s guide to French cheese: Do’s and Don’ts

- Say cheese! Fromages to look out for on your holidays

- Frog’s legs, Snails & Cow udders: 11 of France’s strangest dishes

- The south of France in a glass

- The History of the Michelin Guide