Autumn in Paris means one thing to gourmands all over the city: wild mushrooms! Varied, earthy, and delicious, wild mushrooms are nature’s gift to those courageous enough to hunt for the delicacy in nearby Fontainebleau forest. But centuries ago, mushrooms were suspect at best. And at worst? They were downright scandalous.

The mushrooms available to us at the market all year long, white or brown button mushrooms, are known as champignons de Paris. These “Paris mushrooms” were cultivated in the city’s catacombs and former gypsum quarries starting in the 17th century. By the 19th century, the Paris region had no fewer than 250 mushroom farms!

Unfortunately, metro construction projects starting at the end of the 1800s spelled the end of Parisian mushroom cultivation, and now most mushrooms come from champignonnières, or mushroom-growing cellars, in the Loire Valley, near Saumur.

But long before cultivated mushrooms were popular, wild mushrooms were readily available to those who gathered them in the forest. They were regarded with both reverence and suspicion by superstitious eaters. Hallucinogenic, poisonous, and sometimes deadly, mushrooms grow, according to Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat, author of the definitive History of Food, “in humus, the rotting vegetation found on damp soil” and represented “life regenerated by decay and death.” (Bon appétit!)

And according to medieval food specialist and author of culinary crime novels Michèle Barrière, most all vegetables were suspicious in the Middle Ages because they grew close to the ground. People accused vegetables of tous les maux, or all ills.

The only time I felt ill around mushrooms was many years ago, before the actual mushroom hunt. My foraging friend, keen on keeping his secret mushroom spot just that – a secret – took the extreme precaution of blindfolding me during the drive out to the forest. By the time we arrived to his destination, I felt a little car-sick, even though I hadn’t yet tasted a single mushroom!

Once home though, we cooked up the mushrooms in several different ways, inspired by the different recipes famous chef Auguste Escoffier named “Agnès Sorel.” Just who was this Ms. Sorel, and why are all these French mushroom recipes named for her?

Born in the 15th century, la dame de beauté, or the beautiful Agnès Sorel, became France’s first ever “legitimate” mistress in 1443. Whereas other kings hid (more or less in plain sight) their relationships with other women, Charles VII’s love for Agnès was honored in a great feast and joust in the city of Nancy. There, Charles VII apparently paid off the other jousters so that he would win, thereby earning more respect in the eyes of his beloved courtesan.

Agnès Sorel was the first favourite, or mistress, to be officially presented at the court, and she took full advantage of her power: not only did her beauty stun the king into submission, she proceeded to help Charles VII rule France, and shook up the traditions and values of the day.

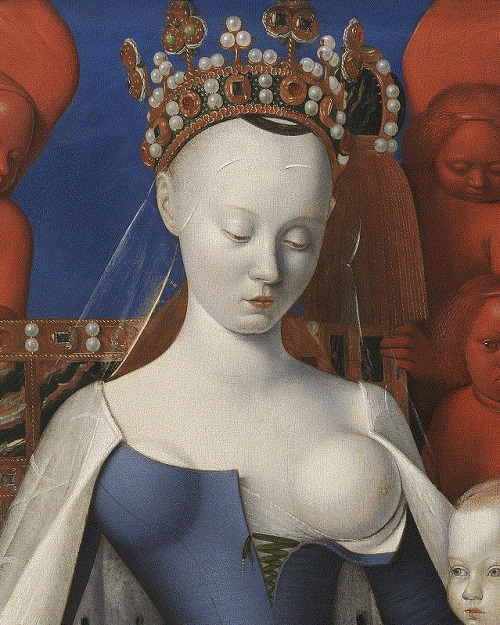

Her style caused scandals left and right: her sable-lined dress trains, sometimes up to eight meters long, surpassed the queen’s in length and luxury. Agnès also outshone the queen by inventing the shoulderless décolleté, characterized as debauched and “representative of weakening values,” according to religious leaders of the time. The ancestor of the bra was born around then, and this bustier délacé or unlaced bustier accentuated a woman’s breasts. (As seen in several renderings of Agnès Sorel, she didn’t seem to need much help in that department.)

Her beauty regime was as impressive as it was unorthodox, at least by modern standards: she used snail saliva to prevent wrinkles, and bathed in donkey’s milk. And her makeup? Ground-up cuttlefish bones served as a fashionably white foundation, and she transformed poppy petals into lipstick. Try finding all that loot at the famous French store Marionnaud!

Even at the table, Agnès Sorel also imposed her sense of modernity: it is said that she was among the first to use a fork, although most accounts of the “devil’s tool” place its importation into France under Catherine de’ Medici more than a hundred years later. Agnès Sorel loved honey and spice bread, invented in the 15th century for Charles VII, and of course, those suspicious mushrooms.

Agnès was what the French would call a gourmande, hiring the best chefs to keep her roi chéri – dear king – in good health. But she never balked at trying her hand at cooking, and allegedly spent a lot of time in the kitchen herself.

Was it for that reason that Escoffier named his mushroom recipes after her? Or simply because France’s first legitimate mistress deserved an equally scandalous legacy? Agnès Sorel even went out with a bang: she died in 1450 of mercury poisoning, and many historians believe she was deliberately poisoned. Her heart is buried at the Jumièges Abbey in Normandy. Next time I visit the abbey, I think I’ll leave a bouquet of mushrooms on her tomb. Merci, Agnès!

Originally published on sister site, France Today