A potted history of the Michelin Guide

We look back on the birth of the esteemed Michelin Guide and its cut-throat star system

It’s been three months since chef extraordinaire Sébastien Bras was stripped of his three Michelin stars – at his own request. His gobsmacking decision sent shockwaves through the industry, the ripples of which are still felt today, and threw into question the legitimacy and purpose of a star system that continues to push even the most assured, and acclaimed, chefs to the brink.

While nonplussed by the award-winning cuisinier’s heartfelt and very public plea to be left out of the 2018 edition – because, in his own words, he could no longer handle the pressure – Michelin relented and duly removed his restaurant, Le Suquet in Laguiole, from its eminent listing. Bras sited three-Michelin-starred chef Bernard Loiseau, whose frantic pursuit of perfection in an already physically and creatively demanding profession allegedly drove him to suicide in 2003, as the chief reason for his withdrawal from the race. And there are countless examples of masterchefs being brought to their knees by a cold shoulder from the all-powerful organisation.

Tough cookie Gordon Ramsay famously wept when his New York establishment, The London, lost both its stars. Others, however, revere the gourmet Bible, which produces close to 30 guides in 25 countries, with just 50,000 hotels and restaurants making the grade. Not least the late Paul Bocuse who once hailed it as “the only guide that matters”.

But how did the fine-dining guidebook (little more than a padded-out road map for decades) and its stringent three-star system become the be-all and end-all of gastronomy, making and breaking careers – with chefs quite literally staking their lives on the Holy Grail?

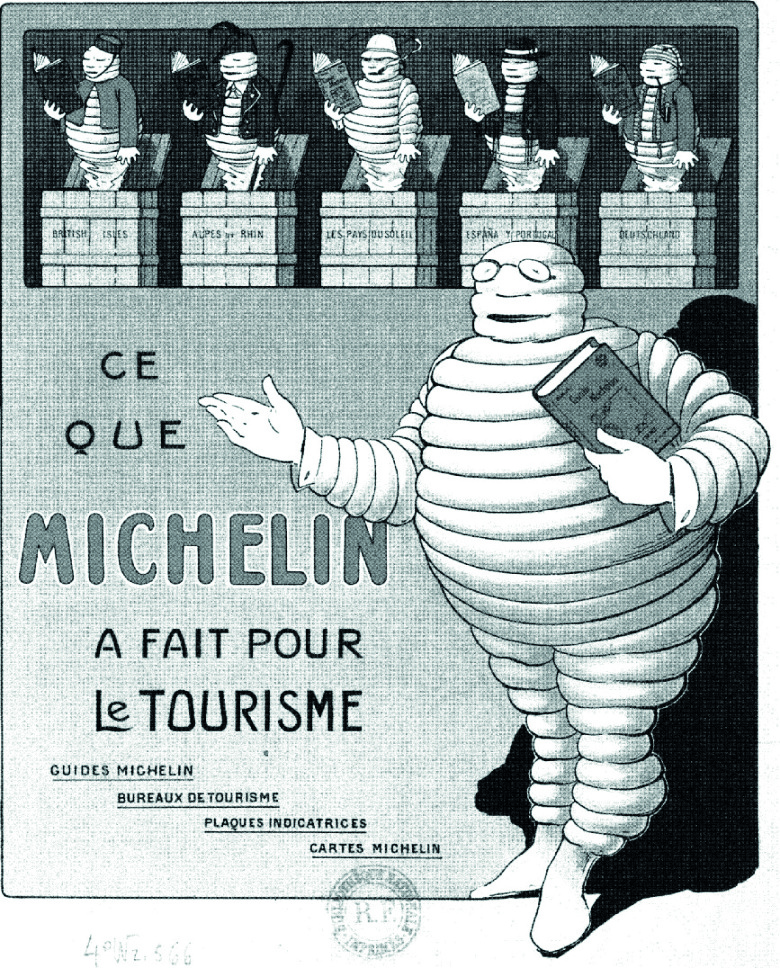

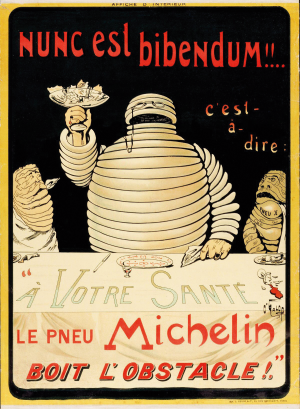

It all started in Clermont-Ferrand in 1889, when brothers André and Édouard Michelin founded their eponymous tyre company, fuelled by a grand vision for the French automobile industry at a time when there were fewer than 3,000 cars in the country. To encourage motorists to burn more rubber on France’s roads they released the Michelin Guide, a nifty booklet filled with maps, tyre repair and replacement instructions and a directory of mechanics, hotels and petrol stations across the nation.

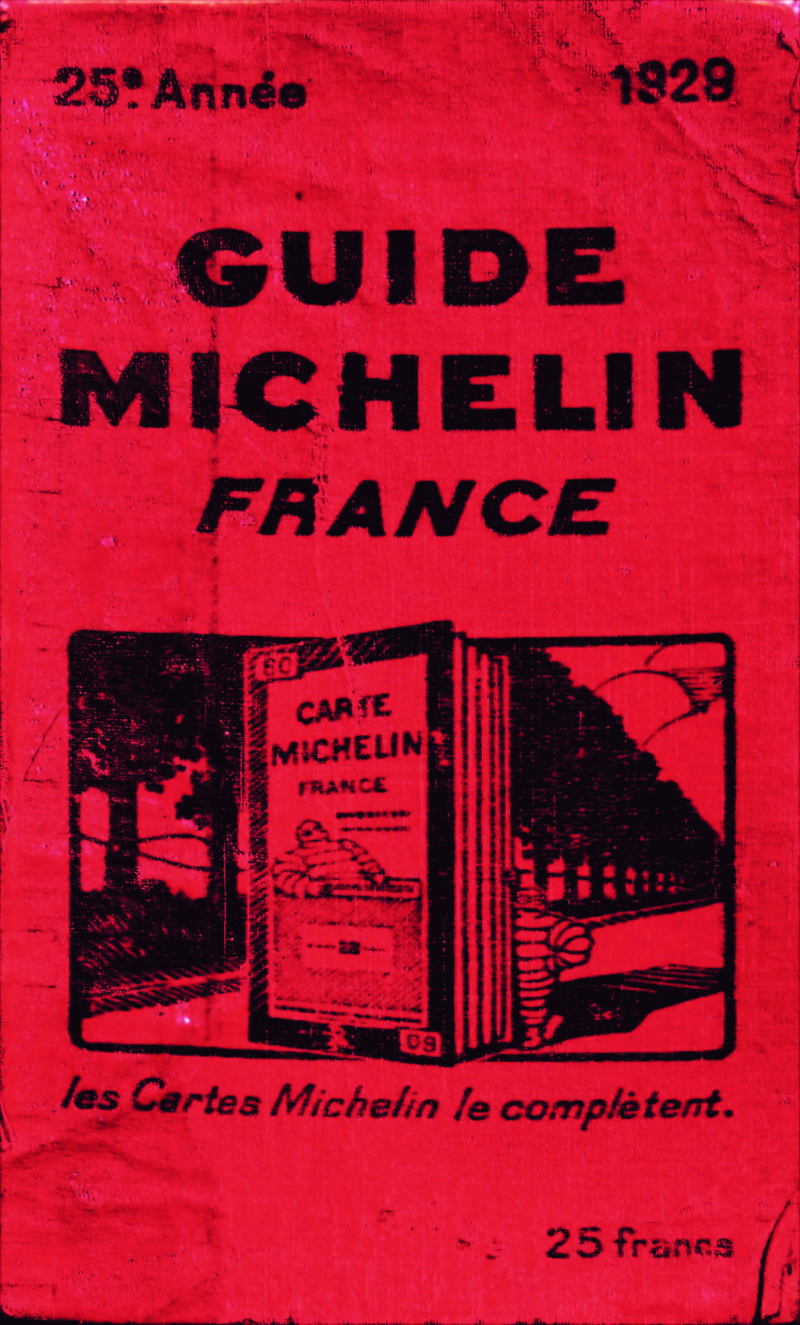

Nearly 35,000 copies of this first free edition were distributed. As the tyre company grew, so did the guide and the wily duo invested in a series of country-specific editions – and in 1920 began to charge seven francs for each booklet. In 1926, the siblings introduced the infamous rating system, though only initially awarding a single star. Five years later, the three-star rating was fully deployed, as was Michelin’s shadow army of exacting inspectors.

IMAGE © AVENTURE MICHELIN

IMAGE © AVENTURE MICHELIN

IMAGE © AVENTURE MICHELIN

Even today, their identity is shrouded in mystery. And you’re unlikely to find photos or other scraps of gen (forget LinkedIn) of the elusive band of critics. Precious little is known about their MO; only that they polish off a minimum of 275 meals a year and spend 160 nights in hotels on average. Quite the tall order. Which is why the ravenous bunch occasionally get mixed up.

Case in point, last year, when the French guide announced to global consternation that a greasy spoon in Bourges, Le Bouche à Oreille, had been awarded a coveted star for its superior fare. One glimpse at the easy-wipe tablecloth and lasagne du jour and it became clear something had gone terribly wrong. The nod was in fact intended for its much snazzier namesake near Paris. In this high-stakes stars game, gaffes are bound to happen occasionally…

Despite all the Bras star-stripping hullabaloo, the French Michelin Guide welcomed new blood to the elite three-star club this year: Marc Veyrat’s La Maison des Bois in Savoie and Christophe Bacquié’s eponymous restaurant in the Var. And Paris remains undefeated as France’s foodie capital with a whopping ten three-star eateries and counting.

Altogether the Hexagon boasts 27 three-star restaurants, including one in Monaco. While a new breed of fiercely independent and award-snubbing chefs is steadily emerging, it’s clear that Michelin is there for the long haul.

First printed in our sister publication France Today

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in Chef, Cuisinier, Gastronomy, Masterchef, MichelinGuide, Michelinstars